The King is Gone

For God’s sake, let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings — William Shakespeare

It seems odd to say, but I’m shocked Arnold Palmer is gone. Sure, I get it. All you had to do was watch those silly Xarelto commercials to see he just how fragile he had become, how time had taken his earthly gifts and pressed them into some cosmic book and put it on the shelf. Earlier the same day, word swept through social media that Miami Marlins pitcher Jose Fernandez had — at the tender age of 24 — died in a terrible and unexpected boating accident. That was shocking, too. But the death of Arnold Palmer at 87 was something else altogether. It’s always a shock when young athletes leave us too early. But, Palmer had been with us for so long, was so embedded into the fabric of the game of golf, that it seemed a given he would be with us forever. Arnold was never supposed to leave us.

Arnold Palmer was not the greatest golfer of all time. He won seven major championships. Jack Nicklaus won 18. Arnold never won golf’s grand slam, that damn PGA forever eluding him, the girl that got away. The PGA Championship has always been the lesser of the four majors and rightly so as I saw it, because if Arnold didn’t have it in his trophy case — how important could it really be?

No. Arnold Palmer was merely the most beloved man to ever walk tee to green. He came along at a time when golf and television began seriously dating. Arnold officiated over that union, making it not just legal, but lasting.

He was the Most Interesting Man in the Golf World. Bear hugs are what he gave the Golden Bear. He was capable of heroic feats of daring do at those most important moments — like 1961 at Cherry Hills, when he roared back in the final round from seven strokes behind to win after a writer named Bob Drum told him in the clubhouse he had no chance.

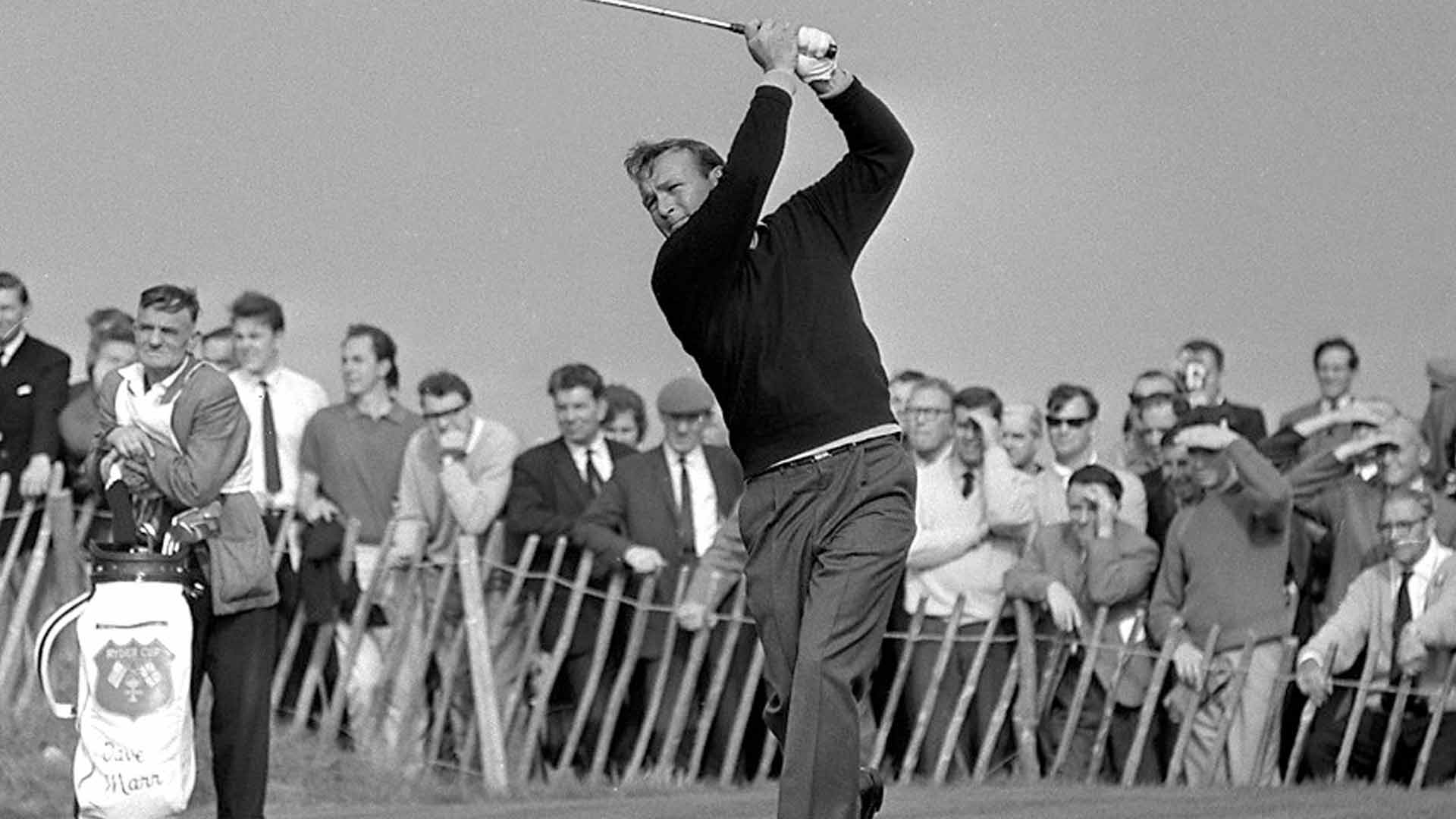

He was James Bond with a 2-Iron, suave and swashbuckling. The hitch of his pants, followed by the flick of the cigarette away, before he settled in over the ball and then commencing that violently beautiful swing ; it was his signature move, like the silhouette of 007 at the beginning of every Albert R. Broccoli production. Surely, Sean Connery, playing golf with Oddjob and Auric Goldfinger, was channeling the King.

Golf was made greater because of the clash of titans that was Palmer vs. Nicklaus. Like Hank Aaron’s quest to overtake The Babe, Jack looked to usurp the throne and was hated by a large portion of the golfing public for it. A young Nicklaus would be labeled “The Fat Man” by the pre-Twitter masses, such was the love for the man from Latrobe, Pennsylvania.

Palmer almost singlehandedly made the British Open relevant again. For years, American golfers refused to travel across the ocean to play in golf’s oldest championship. They had become fat and somewhat arrogant, unimpressed by the meager winner’s purse and lazy at the very thought of negotiating a links-style course an ocean away. In 1959, not a single American played in the Open at Muirfield. A year later, Palmer would play in The Open at St. Andrews, a pied piper parting the Atlantic, leading the U.S. back to Great Britain, knitting back together the rich history of the game.

“It was exciting for me because I was trying to fulfill a desire that I had to play in the Open Championship, and I felt that if you were going to be a champion, you couldn’t be a champion without playing in the Open and hopefully winning the Open.”

He was the Elvis of Golf, making the game sexy, his charisma working its magic not only on women, but men, too, who all wanted to be like the King. Just as Presley was known exclusively by his first name, “Arnie” could only mean one man. Elvis and Arnie. Two men, each on the throne of their respective kingdoms.

He was Tiger Woods before there was Tiger Woods. The son of a groundskeeper, his free time as a boy was spent on the course after it was closed for play at the end of each day. Before we went slack-jawed over the adoring mobs following Woods from tee to green, there was Arnie’s Army, crowding the ropes, straining to catch a glimpse of the great man.

I think the King is but a man as I am

The violet smells to him as it doth to me.

If you were a golfer of a certain age, you saw yourself in Arnold Palmer. The swing was far from perfection. It had none of the methodical look of Jack’s famous Michelangelo-like creation, or Ben Hogan’s precise, stone tablet construction of a swing. It was furious, almost flailing. It wasn’t country club smooth. It was public course real. Mostly, it looked approachable, like the man himself. Yes, he was Bond. Yes, he was Elvis. Yes, he was bigger than life. But he had that touch of the common man inside him. He walked the rope lines and you knew him, even as you never had met him. He was relatable. He felt like one of us, even if in truth he was anything but.

I learned the game of golf at my father’s knee. He grew his love of golf from a man named Charlie Oldendick. Charlie was not family in an ancestral sense, but surely was by all other measure. My first memories of golf were chipping in Charlie’s front yard with a rusty old 9-iron. For reasons I cannot explain to this day, when I think of Arnold, I always think of Charlie and my dad. Standing on the 16th tee at Pebble Beach with my father—a trip of a lifetime—I wondered out loud what Charlie would think if he could have been there with us that day.

. . .

Now, he’s with us always. We’ll hear him in the clack-clack of our old metal spikes as we head down the parking lot to the practice green. We’ll feel him in the touch of the worn leather grips we should have replaced seasons ago. We’ll see him in the footprints marked in the dew that covers the greens first thing in the morning. Maybe we’ll linger on the first tee, waiting a moment longer for a familiar face to round the corner out the clubhouse door.

I never met Arnold Palmer. Still, like millions of weekend golfers, I feel comfortable saying, “goodbye, my friend,” even as I know he’ll never truly be gone as long as we have our memories and golfers keep score.

No Comments