The Barbarians at the Gate

The fault line between Old School and New School may have been breached once more

First they came for the Bunts, and I did not speak out —

Because I was not a manager.

Then they came for the RBIs, and I did not speak out —

Because I was not a hitter.

Then they came for the Closers, and I did not speak out —

Because I was not a pitcher.

Then they came for me — and there was no one left to speak for me.

. . .

There are these moments. Some trumpet their arrival. Most slip by unseen. What did Malcolm Gladwell call them? Tipping points?

“…that magic moment when an idea, trend, or social behavior crosses a threshold, tips, and spreads like wildfire.”

Baseball has had its share of tipping points throughout its history. Think of a time when strategy and speed were the order of the day. Then Babe Ruth came along. Think of Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson, human tipping points who changed not just how the game was played at the major league level, but who played it.

Baseball’s tectonic plates are always moving, always shifting beneath the surface of the game. We tend to notice them more during the postseason, for obvious reasons. It appears we are on the cusp of another dramatic shift this fall. This isn’t merely a tremor, it’s a seismic event, pushing the needle into the red; forcing us to rethink how we see the game once more. The actors involved have exotic names like Showalter and Francona; everyday names like Miller and Jansen.

This time the war is about tactics, as it always seems to be these days, the little battles that wage inning to inning, batter-by-batter. Baseball is less and less about shopworn shibboleths handed down from one generation of ballplayer to another. Now, it’s about the granular, the moment-by-moment struggle to gain the smallest of advantages, panning the infield dust for the nuggets of information that slip by the less inquisitive, there to be scooped up by those opportunistic enough to recognize them and turn them into small edges, and hopefully, postseason gold.

It’s about Process over Results. That’s what the Geeks trumpet, to the chagrin of the Gatekeepers. Call it Sabermetrics. Call it Moneyball. Revel in it or recoil from it. It is now the currency of the game, so much so, that even the men in the suits high up in the owners’ boxes are stars. Make no mistake, the talk this postseason will be about a guy named Theo every bit as much or more than it will be about Aroldis Chapman, Kris Bryant or Clayton Kershaw.

Oft-times, Process is trammeled up by the moment, the “now” overtaking reason. Hard on the heels of Buck Showalter’s failure to use his best reliever in an elimination game came Terry Francona, one of the few managers today who understands and embraces the true meaning of “high leverage.” Irony abounds. Showalter is among the game’s brightest minds. This egregious misappropriation of resources was something normally associated with Ned Yost, not Buck, for god’s sake.

For the average manager, high leverage situations can be summed up in two words: NINTH INNING. Relief pitchers have roles, roles frozen in carbonite. Closers are Jedi knights, rare warriors who navigate the asteroid field that defines the last three outs of a baseball game. Give them the ball in the mythical ninth we’re told — and never tell them the odds.

. . .

“There aren’t many lockdown closers around. That’s a hard job. I think that’s one of the hardest jobs there is, to take that final breath out of anybody.” — Dusty Baker on Nationals’ closer Jonathan Papelbon

Francona is of another breed. He knows high leverage moments begin not just before the ninth, but immediately after the National Anthem is sung. That’s why in Game 1 of the American League Division Series, the Indians’ skipper summoned his Jedi — Andrew Miller — not in the 7th or 8th inning, but in the 5th, when he believed his starter, Trevor Bauer, might be a spinning top about to wobble. Even if some in the Sabermetric community raised an eyebrow, questioning the urgency of that particular moment, they held their collective tongue, giddy that Francona’s insurrection was finally happening in the white-hot crucible of postseason baseball, out in the open where no one could look away. Not this time.

The unsung hero was closer-in-name-only Cody Allen, who held the Red Sox in check, barely. How important was Allen? Had Allen faltered, Process would not have led to the desired result. Oh, how the Gatekeepers would have crowed:

So hilarious seeing these stats heads get so worked up about Buck’s bullpen moves. You mad dudes? Experience & instinct > your spreadsheet.

— CJ Nitkowski (@CJNitkowski) October 5, 2016

But Cody Allen did not fail. Instead, he screwed his courage to the sticking place, there on the pitching rubber. Days later, Miller and Allen would repeat their performances, ending Boston’s season and Big Papi’s career once and for all, validating their manager’s decision-making; keeping the Gatekeepers off-balance for another day.

If only Twitter ran MLB bullpens, the world be a better pl…just kidding. No mas por favor. pic.twitter.com/ivPtx2SefB

— CJ Nitkowski (@CJNitkowski) October 11, 2016

. . .

This first week of 2016 postseason baseball was merely preamble for Game 5 in Washington between the Dodgers and the Nationals.

Irony abounds. Here was Dusty Baker, one foot at the top step of the dugout, at the vanguard of the Old School, facing yet another deciding game, the ninth straight in which he would come up a little short.

Dusty Baker is a thoughtful man. A man of conviction. He has this metaphorical book he carries everywhere with him: the Book of Hank. Baker broke in with the Atlanta Braves and played for eight seasons with Hank Aaron, who took the callow Californian under his wing. Much of what Baker believes about the game and how it should be played comes from those formative years with Aaron. Washington baseball fans are just now becoming familiar with the Book of Hank, as Cincinnati fans once did and Chicago fans before them. Baker, once handed a rare lightning bolt of a pitcher, a Cuban named Aroldis Chapman, chose to use him in the most Hank of ways, the myth of the closer being a dog-eared chapter in that old. yellowed book.

Dusty has always had a penchant for staying with his veteran starting pitchers a bit too long, so it was out of character to see him here, in such a crucial moment, removing Max Scherzer after 99 pitches and six innings, having given up one measly run. But remove him he did.

Meanwhile, Dodger manager Dave Roberts took up the mantle left by Terry Francona, brought in his closer, Kenley Jansen in the 7th, making mouths at the invisible event, asking the impossible, which is what Jansen delivered: 7 outs, 51 pitches, with Jansen clearly laboring at the end until Kershaw arrived, his own postseason legacy hanging in the balance — and saved the Dodgers’ season.

So, Clayton Kershaw gets the first save of his career. Irony abounds. The “Save” is what got us into this mess to begin with. In 1960, a fine baseball writer by the name of Jerome Holtzman invented the Save. By 1969, baseball would make the Save an official stat. Before long, sports agents would begin backing up the Brinks truck for their clients, because once you start assigning an outsized value to the final three outs of a baseball game, people are going to start asking to get paid for that service.

Tony La Russa turned Dennis Eckersley into his own personal pitching Frankenstein; and the closer was officially here. Specialization ruled the day. Relievers became packaged commodities—7th inning specialists, 8th inning machinists, lefty one out guys (LOOGYs) formed the conga line proceeding those ninth inning caped crusaders . Now, it looks like it’s heading back in the other direction. Maybe.

Fangraphs’ frontman Dave Cameron said as recently as last year:

“This change will likely occur at a glacier pace, but it is beginning.”

Well, the game is experiencing its own version of climate change. The heat of the postseason moment has accelerated the melting of old methods. Eighteen months later, baseball is on the verge of being in a new place.

Irony abounds. Little about this supposedly avant-garde usage of bullpens is particularly new. In 1976, Rawly Eastwick of the Cincinnati Reds would win the first National League Rolaids Relief Man Award, working nearly 108 innings, while Bill Campbell of the Minnesota Twins won in the American League, tossing a staggering 168 innings, while winning 17 games, losing 5. The trophy, which looked remarkably like the Lombardi Trophy with a fireman’s helmet slapped atop it, celebrated men who came into the game in high leverage situations in the 6th, 7th and 8th innings, then stayed to finish the job.

. . .

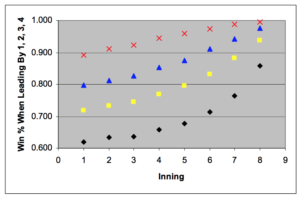

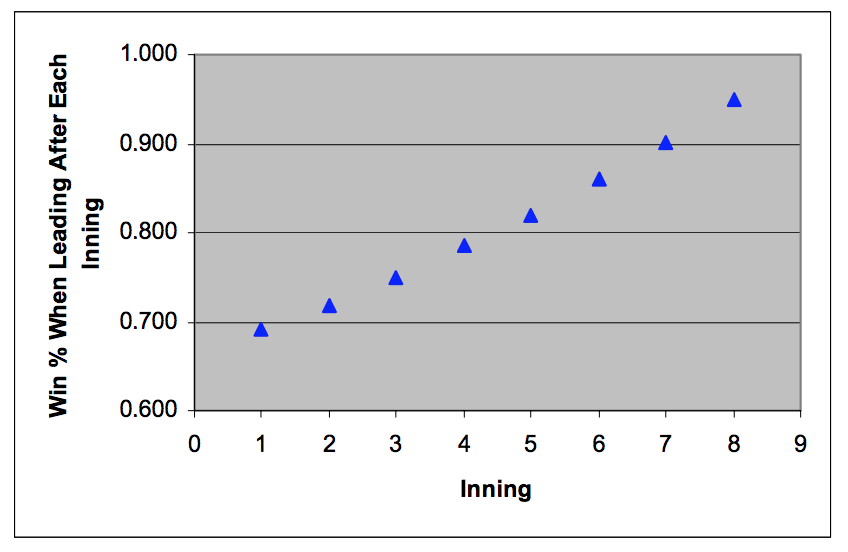

The winning percentage for teams entering the 9th inning — that moment , as Dusty Baker so vividly stated, where only special men possess that right stuff to “take that final breath” from the opposition—has remained remarkable constant over the last 100 years. The reality is that whether the man taking the hill was named Mariano Rivera in 2010, or Virgil Trucks in the 1950s — a team’s chances of winning really fluctuated very little. Whether it is a one-run lead, a two-run lead, or a three-run lead heading into the ninth, teams have converted those leads into wins 85, 94 and 96 percent of the time, respectively, as analyzed by David W. Smith at Retrosheet:

What Terry Francona knew when he sent Andrew Miller to the mound in the 5th inning of Game 1 of the ALDS was a simple truth: getting to the 9th inning WITH a lead is more important than worrying who will take the mound to eventually protect that lead.”

In fact, to take this trend one step further, Mr. Smith’s findings show that “teams which lead after one inning win nearly 70% of the time and the winning percentage gets consistently better with each passing inning.”

Whoa. Should teams be deploying their best relievers even earlier? Should they begin the game? Is your mind blown yet?

At the very least, we might be heading back to a version of those bygone Sparky Anderson days of managerial quick hooks and proactive pitching moves as more young, progressive GMs take the reins of major league baseball teams. The Kansas City Royals success with their unique bullpen approach in 2014 and 2015 have had other franchises taking a hard look about how they might build their bullpens moving forward. But, it’s important to understand that this is happening not because of Process, but because of Results and where those results are playing out: on a national stage. Yes, the Process is solid. But, beware. Should Process falter during these small sample-size days of autumn, should Jansen and Miller fail or the relievers that follow them buckle, an old school culture will surely rise up and retrench. In a final irony, the players that follow these famous high-leverage stars, players like Cody Allen, Bryan Shaw, Pedro Strop and Travis Wood, may turn out to be more important to changing he way a team’s best relievers are used than Andrew Miller or Aroldis Chapman.

So, there’s still a long way to go. But as a recent Nobel Prize winner once said, “the times they are a-changin’.”

1 Comment

Good day!

You Need Leads, Sales, Conversions, Traffic for richard-fitch.com ? Will Findet…

I WILL SEND 5 MILLION MESSAGES VIA WEBSITE CONTACT FORM

Don’t believe me? Since you’re reading this message then you’re living proof that contact form advertising works!

We can send your ad to people via their Website Contact Form.

IF YOU ARE INTERESTED, Contact us => lisaf2zw526@gmail.com

Regards,

July 21, 2019 at 8:26 pmFerrell